One of the unfortunate truths about archaeology is that most of the time, the artifacts we find are broken. This is especially true for artifacts made of fragile materials, such as glass. However, every now and then everything comes together to preserve a whole glass object in the ground where it can be found later. That is how, on November 11th, 2023, the excavation crew at St. James AME Zion Church found a Royal Salad Dressing bottle underground in the yard, completely intact. The bottle was discovered in Unit 6, an area towards the north end of the yard that was potentially a trash deposit based on this and other artifacts recovered there. Now, it makes an excellent case study to explore how archaeologists use historical sources to assist in interpreting artifacts. The analysis will start with learning about what is written on the bottle, then assessing how it was made, and finally looking for contemporary accounts of the product it contained to see how people might have viewed it when it was used at St. James AME Zion Church. The bottle stands 18.4 cm (7.2 in) tall and 6.5 cm (2.6 in) wide at the base. It is made entirely of clear glass, with embossed words on the side and bottom, as seen in the pictures below.

The bottle stands 18.4 cm (7.2 in) tall and 6.5 cm (2.6 in) wide at the base. It is made entirely of clear glass, with embossed words on the side and bottom, as seen in the pictures below.

Figure 1. Royal Salad Dressing Bottle (photograph by author).

Because the words are the same material and color as their background, they can be hard to make out in pictures, so here is a transcription of the side:

ROYAL SALAD DRESSING

HORTON-CATO

FC. Co.

DETROIT, MICH.

This gives the name of the product that the bottle was made to contain, the manufacturer, and the city where they manufactured the bottle. That is already more information than most artifacts offer up front, but it is not all that was written on the bottle. There is also embossed text on the bottom, again followed by a transcription because the glass can be hard to read in pictures:

Figure 2. Royal Salad Dressing Bottle Base (photograph by author).

PATENTED

1289

APRIL 25TH, 1882

This does not give a manufactured date, but instead the date a patent related to this bottle was issued by the US Patent Office. Unfortunately, the meanings of “FC. Co.” on the side and “1289” on the bottom are both still unknown. However, there is a substantial amount of information that can be gleaned from the text that is understandable.

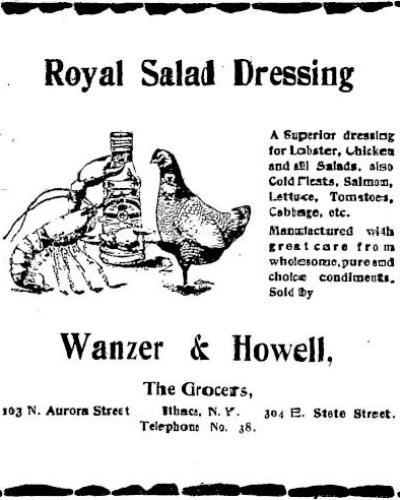

Starting at the top, Royal Salad Dressing was the brand name of a seemingly popular dressing advertised for “Lobster, Chicken, and all Salads; also Cold Meats, Salmon, Lettuce, Tomatoes, Cabbage, etc.,” and it was sold in New York.[i] We know it was sold there because there are advertisements for grocery stores selling it in newspapers in Ithaca, NY. If we did not have that evidence, we could not say for sure that it was sold in New York because the bottle could have been brought into town by someone traveling from another state.

Horton-Cato is an abbreviation of The Horton, Cato Mfg. Co. Hyphenating brand names for embossed glass was especially popular in the years after 1900, and Horton- Cato went through several name changes over the years. It is unknown what the next line, “FC. Co.” means, and the last line on the side, “Detroit, Mich.” is most likely because Detroit, Michigan is where Horton-Cato had their headquarters and manufacturing center for their products.

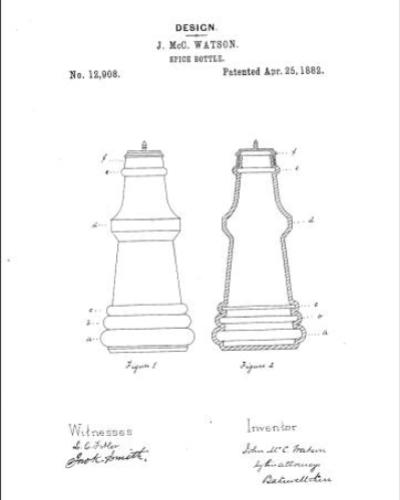

The text on the bottom required looking at patent records for the date given, April 25th, 1882, to see what it was referencing. There were four patents given on that day that were related to bottles, but a design patent for a spice bottle design is what this bottle is referencing. The application described three stacked rings around the lower part of the bottle, the bottom one being larger than the base of the bottle and then getting smaller as they went up; the taper of the bottle from the top of the rings up to the shoulder; and the taper of the neck from the shoulder to another ring just below the mouth of the bottle where a screw-cap could be used. This design drawing is not identical to the design later used by Horton-Cato for their dressing bottles, but the important features are all there, as seen in the image from the patent application below compared to the picture of the bottle.

Figure 3. Design for a Spice-Bottle.[ii] Compare to Figure 1.

Therefore, to mention the patent on their product, the company must have purchased or licensed the patent from the person who applied for this patent after he got it in 1882. This patent was important to their product because they were advertising the Royal brand as a high-end experience and they wanted a glass bottle that would stand out and be appealing to look at on its own, which this design accomplished.

One thing to note is that the bottle gives the patent date, not a manufacturing date, and they could have used this patent for years. Therefore, other methods must be used to find when this bottle was actually manufactured. Luckily, glass making went through several stylistic and technological shifts near the turn of the 20th century, so we can look at marks of how it was made to narrow down when it was made. This is not an exact science because people may use older methods if they are easier or cheaper and trends do not have exact years where they start or stop, but it can be reasonably accurate, especially when paired with other external evidence that we can evaluate and compare this with.

To attempt to date the bottle, the Historic Glass Bottle Identification and Information Website promoted by the Society for Historical Archaeology and the Bureau of Land Management was consulted. The bottle has a noticeable side mold seam going up and down on either side of the embossed text, but it disappears on the screw threads right before the very top of the lip, so it is most likely “mouth-blown,” or hand- made. This style became very uncommon after 1915, as machines grew in popularity, but it dates back through most of the 19th century. The next thing to look at is the base. It does not have a pontil scar, a mark left on the base of a glass object from the metal rod used to hold it while the opening is widened, so it was likely made after 1865. At that point, there were several inventions to hold the bottle during creation without leaving marks on the bottom, so the potential date of manufacture is narrowing to the 50 years between 1865-1915. The bottom of the bottle also does not have a mold seam running through it, that is only on the sides, so it was likely made with a cup bottom mold holding it which was most popular from the mid-1880s to the late 1910s. The last diagnostic trait to look at is air venting marks on the bottle. These are tiny pinpricks of air where the glass was poked to allow air to escape during its creation that then sealed up because the glass was still so hot it was a liquid. They do not show up well in photographs because they are so small, but there are several around the mold seams and around the body of the bottle. As time went on with mouth-blown bottles, more mold air vents were used. Having several means this bottle was probably made later, starting around 1905. Looking at all this information together shows that this particular bottle was likely manufactured sometime between 1905-1915, making it over 100 years old!

In order to look more at how Royal Salad Dressing was perceived by the people who bought it, we rely largely on newspaper advertisements and a book describing businesses in Detroit in the late 19th century, Detroit in History and Commerce. The author, James Mitchell, talks about Horton-Cato as producing “fine table condiments” and says “the Royal Salad Dressing is not surpassed by any in the world…Their entire line of high grade table goods are not anywhere surpassed in character and general desirability.” For another perspective of how this product was seen, we can look at advertisements for it in the local newspaper. Here is one from the Ithaca Daily Journal on May 5th, 1900:

Figure 4. Wanzer & Howell, advertisement.[iii]

Here, a grocery store had a memorable image to grab people’s attention and then advertised itself entirely based around the fact that they carried Royal Salad Dressing. This speaks to how popular this salad dressing was for people. They also described the dressing as “superior” and said it was “manufactured with great care from wholesome, pure and choice condiments.” Another advertisement in that same newspaper, several years later and for a different grocery store, shows prices for different sized bottles:

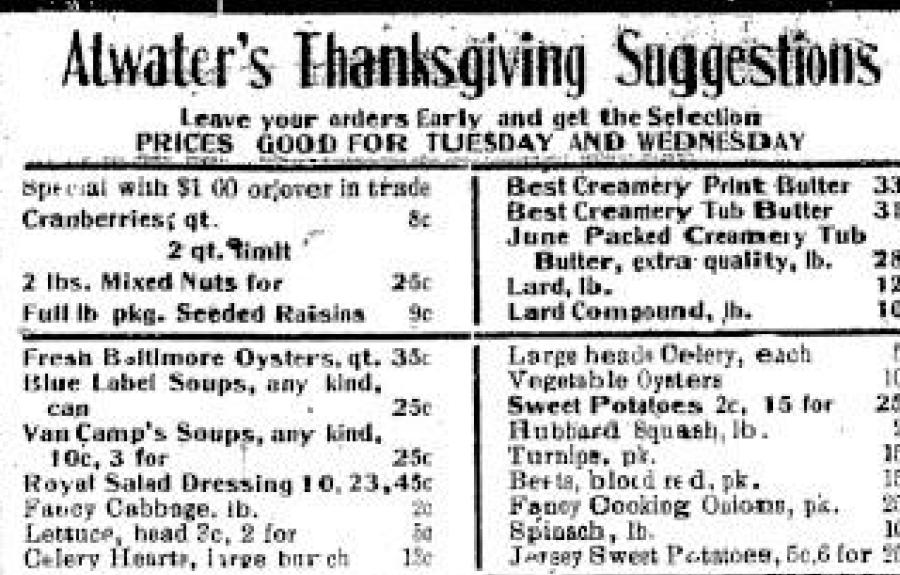

Figure 5. Atwater, advertisement, 1906.[iv]

Atwater grocery store advertised this product on a list for Thanksgiving suggestions, indicating that it could have been perceived as nice to use for major holiday meals. They also listed three prices next to it. Based on newspapers outside Ithaca, those were for the three sizes of bottles that Royal Salad Dressing came in: small size, ½ pint, and 1 pint. It is not clear how small “small size” was, but that information is not relevant for this analysis because based on measurements taken of the bottle found at St. James, it would have been a ½ pint, or 8 oz., bottle.

This means that members of St. James could have purchased a bottle this size for Thanksgiving in 1906 for only 23 cents. It is exciting to consider that since 1906 is within the time frame the bottle is thought to have been manufactured within, they could have bought it based on this exact advertisement. That price is roughly eight dollars in 2024, making it significantly more expensive per ounce than most salad dressings today if it were to be sold at the same price adjusted for inflation. It is also much smaller than most containers now, with 16 oz being a much more common size for salad dressing containers. The price for Royal Salad Dressing was higher than other salad dressings, when it was listed alongside other options in advertisements, which adds more evidence to the idea that this was valued by people for its quality and might have been considered a luxury item.

Gaining all this information and insight about one object based on research of newspaper advertisements, glass manufacturing practices, and more written texts is incredible. Those sources cannot always assist with archaeology because sometimes the artifacts are too fragmented or the sources do not exist. It is a big perk of historical archaeology to have those available for research and lucky that in this case the bottle held together well to be analyzed. Now we know so much more about this salad dressing bottle found at St. James, and we can better interpret how the people using it felt about it.

References:

[i] Wanzer & Howell, The Grocers. “Royal Salad Dressing.” Advertisement. Ithaca Daily Journal, May 5, 1900. NYS Historic Newspapers.

[ii] Watson, John McC. Design for a Spice Bottle. US Patent 12,908, filed March 20, 1882, and issued April 25, 1882. https://patents.google.com/patent/USD12908S.

[iii] Wanzer & Howell, The Grocers. “Royal Salad Dressing.” Advertisement. Ithaca Daily Journal, May 5, 1900. NYS Historic Newspapers.

[iv] Atwater. “Atwater’s Thanksgiving Suggestions.” Advertisement. Ithaca Daily Journal, November 27, 1906. NYS Historic Newspapers.