We’ve been busy this Fall with the final season of community-engaged excavations at the St. James AME Zion Church in Ithaca. We’ve opened up the ground in a new 1 meter by 1 meter square very close to the western door of the new church kitchen currently being constructed. This new area is within a couple meters of the western wall of the church, sitting squarely outside of where the parsonage used to be. On only the second day of excavating in this new area (called “unit 8”) among fragments of stained window glass (of the same kind written about in a previous blog post) and unidentified shards of bottles, a surprisingly large glass lid was unearthed around a foot (30cm) deep. It was found in the northern quarter of the unit, around 40cm from the west end was immediately striking because letters could clearly be seen. The glass fragment left the ground on Saturday the 21st of September as was initially cleaned and photographed on October 2nd. Take a look!

Figure 1. Glass Fragment (photo by author).

The glass fragment, which is described by collectors as ‘aquamarine’ in color, and which is very translucent, appears to read “[…]ANSEY•GLASS•MANU[…]” on the outer row and “PATENTED•JAΛ[…]” on the inner ring. The first fully visible letter on the outer ring is almost certainly a capital A, and the last letter on the inner ring would make sense as “JAN” – as in “patented in January” (Figure 1).

Consulting lists of known glass manufacturing companies and their maker’s marks, we can see who might have embossed these letters on a glass lid. Because we don’t have the start of the company name (only the “-ansey” that it ends with), we’ll have to look through all the possible companies. Thankfully, these databases are all digitized, so we can quickly find that the only glassmakers in the database with an “-ansey” in their name are those belonging to the “Cohansey Companies” group. Of these 8, one is listed as the “Cohansey Glass Mfg. Co.” If we didn’t have the “A” at the very beginning, or if we were unsure that this were really an “A”, only one company not in the “Cohansey” group comes up: “Munsey Glass Co.”, Given the options, it seems safe to attribute this glass fragment to Cohansey Glass Manufacturing Company, which operated in Bridgeton, New Jersey from 1870 to 1901. And who embossed their glass lids with capital letters reading “[COH]ANSEY GLASS MANU[F. CO.]”. If you look very closely, the bottom right corner of the H and the bottom left corner of the F can almost be seen on the lid.

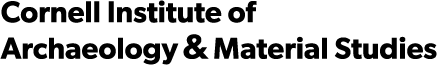

Thanks to writings accessible on the the Historic Glass Bottle Identification and Information Website of the Society for Historical Archaeology, we can read all about the interesting history of not just this glass factory but the people behind it. Looking through the patents registered to the Cohansey companies when they operated under that name, we see the only possible “JAN” patent was issued to Thomas Hipwell on January 18th, 1876, for the “Hipwell-style” lid (also called the “Cohansey Closure”) (Figure 2). The patent number 172,316 was for an “Improvement in Fruit-Jar Clamps, and quickly went into manufacture. The Cohansey Glass Manufacturing Company was bought by the American Window Glass Co. by 1902 during a large acquisition including 40 glass factories in the area. This gives us a very nice window from January 1876 to 1902 during which this jar lid was likely made.

Figure 2. Hipwell Clamp Patent.[i]

The latest record of fruit jar productions at the Bridgeton factory was 1899 while by 1900 they seemed to have no fruit jars in production, which makes our window ever so slightly smaller (1876-1900).[ii] This 1876 patent was a fairly big deal in the world of fruit jar closures, as it meant you could make a jar without a groove in the lid, making the jar stronger and less prone to breaking. This patent seems to have been their most popular, and seeing a jam jar from a New Jersey glass factory turning up in Ithaca shouldn’t be all that surprising given how well the Cohansey jars were selling during their heyday. What’s particularly interesting to consider is whether this jar came to Ithaca – and to St. James – empty or bearing fruit.

Regardless of the journey it took, well-made jars with a firm and watertight closure were far from a single-use item! They might see decades of use and reuse if nothing bad happened. Surviving jars of this kind are a fairly popular collector’s item, with lots of different pristine condition Cohansey jars using the 1876 lid selling for auction these days in the U.S. Here’s an image from Etsy of a very similar ‘type 3’ lid associated with a quart jar (Figure 3). It was listed in May 2022 and sold for $74.24. All sorts of different sizes of jars might fit with this lid; we hope to learn more about these jars soon.

Figure 3. Jar For Sale on Etsy.[iii]

There are only two types of jar lids that have been found which are associated with the January 18, 1876 patent, which are straightforwardly called the type 3 and type 4 lid. The type 3 have a cross-hair pattern (like ours does) while the type 4 has flat glass in the center, meaning our lid is almost certainly a type 3. On the reverse side of our jar lid (Figure 4), we can see another unclear mark – A, V, M, N perhaps? From images of the different types of Cohansey lids, we can see that “M” is printed on the reverse side of the ‘cross-hair’ of the Type 3.

Figure 4. Reverse view of lid (photo by author).

Other letters have been found on the reverse side of type 3 lids – including R, H, and X – while some have been found without letters. It’s unclear what these letters refer to, …

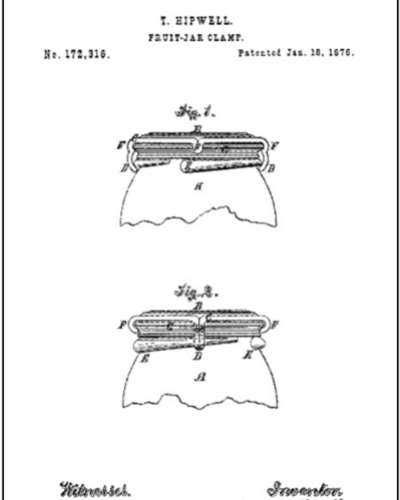

I couldn’t find any ads contemporary to the post-1876 lid and jar, but this ad from the June 29th, 1875 edition of the Reading Times shows how these jars were being marketed and sold. We can also see what these jars look like today thanks to the excellent preservation of jars kept and sold by collectors.

Figure 5. Advertisement for Glass Jars.[iv]

These three jars pictured below are from the same 1876-1900 period of Cohansey fruit jars and are of the same aquamarine hand-blown glass that Cohansey was known for. This gives us a fair sense of what kind of jar this lid once kept sealed tight, and the visibility it gave people of the contents safely held inside. These glass jars are made in a mold, with two mold seams on either end of the jar, by blowing molten hot glass into a metallic mold.

Figure 6. Glass Jars.[v]

The lids are ground down by hand to fit tightly with the mouth of the jar. The resulting seal helps ensure that fruit and fruit preserves can stay fresh and secure from the prying hands of fruit flies and ants. There are all sorts of different glass fragments that have been found in the ground, just one week after the glass lid found the light of day, another similarly thick aquamarine glass fragment was unearthed. It was found in the same area of unit 8, two loci (or layers) and less than 10 centimeters below. This was especially exciting at first, because this might have been from the same jar – after the fragment was documented in situ, and excavation continued, it became evident that this was not the case.

This fragment (Figure 7), which appears to be the base of some kind of bottle, is much thicker than the one found a week earlier - which is surprising, given how bulky and thick the Cohansey jar lid is. It seems to have been made in a completely different fashion, evidenced by its extremely rounded internal walls and the presence of very small bubbles inside the glass which are indicative of the mouth-blowing techniques that were decreasingly popular with bottle makers through the late 19th century.

Figure 7. Preliminary Field Photo (photo by author).

From its shape and size, it could belong to all different sorts of 19th century vessels, most of which are under the category of ‘druggists’ bottles. These were intended to hold medicines, poisons, cures, and tonics, as they were suited to hold a whole variety of different household chemicals. It’s a fairly small base, and it fits the SHA description of ‘oval’-shaped best, even though it’s not shaped as a strictly geometric oval (but more like a heavily rounded rectangle). If we are to follow the SHA guidelines for assessing the date of this fragment, and if we feel comfortable describing it as the base of a druggists bottle, it seems to fit the description of ‘crude glass’ featuring ‘copious bubbles in the glass’ that characterizes druggists bottles before the American Civil War.

However, we don’t see any evidence of a pontil scar (see an earlier blog post for more discussion on pontil scars) on the base or any scars from machine or suction molding. There are no visible mold seams on the base or on the sides where they meet the base (called the ‘heel’), so there’s very little reason to think that this wasn’t mouth-blown, as initially suspected. All we see is this proudly embossed letter F on a smooth surface, so there is a good chance that this bottle belongs to the 95% or so of bottles without pontil scars which date to after 1865. It’s important to note that this kind of analysis is less precise – this base could date all the way back to 1850, or possibly before, but as it stands right now, we’d have to do more research to reach a better understanding of what kind of vessel this fragment may have come from and when it may have been manufactured.

The F on the base of this small bottle is so far a conundrum for our classification, as no glass makers have been found to use this mark on the bases of this kind of vessel. The Fairmount Glass company or the Owens company may be a good first guess for the culprit. They both produced glass bottles with a similar letter F on the base, yet neither of these companies produced old-fashioned mouth-blown glass bottle of this sort, instead using 20th century machinery that produce glass with walls of much more even thickness, and with clear and obvious signs of 20th century machine molding on the base.

These are only the most striking and immediately interpretable glass fragments from just the first few weeks of a new unit. The story of the artifacts in this unit are only just beginning, and we hope you enjoyed reading about how much we can learn from just a handful of incomplete letters on some chunks of glass. If anything in this was interesting to you, or if you had something you wanted to share with us at St. James about old jam jars and medicine bottles, we’d be happy to hear about it!

References:

[i] Lockhart et al. 2014, Figure 6, “The Cohansey Companies,” The Encyclopedia of Manufacturers Marks on Glass Containers. http://www.sha.org/bottle/pdffiles/Cohansey.pdf.

[ii] Caniff, Tom; 2000; “The Versatile Cohansey.” The Guide to Collecting Fruit Jars: Fruit Jar Annual, edited by Jerry McCann. Vol 5. Privately published, Chicago.

[iii] https://www.etsy.com/listing/1169056389/vintage-aqua-blue-cohansey-quart-jar?show_sold_out_detail=1&ref=nla_listing_details.

[iv] New Cohansey Fruit Jars advertisement. – Reading Times, June 29, 1875, via https://fohbcvirtualmuseum.org/galleries/jars/cohansey/.

[v] https://fohbcvirtualmuseum.org/galleries/jars/cohansey/.